Driving Sideways

The Story of a Band

by Henry Ayrton

The Story of a Band

by Henry Ayrton

4) Travelling Band

Something that was very characteristic of bands in the mid-to-late 1960s, from The Beatles right the way down to The Stark Electric Blues Band, was the speed with which changes took place in both personal appearance and musical style. As far as personal appearance was concerned, everyone in our band steadily looked more scruffy and dissolute as time went by (except for Tad, who’d always looked that way). The most extreme example was Terry who had, when he joined us, very short hair that even a recruiting sergeant might have raised few objections to. After that, though, he simply stopped having it cut and it grew longer and longer until he gradually disappeared behind a cascade of hair when bent over his drum kit.

As far as our style in music was concerned, the presence of Tad & Neil in the band provoked a gradual move towards original material. This process accelerated once we’d expanded from a six- into a seven-piece outfit. Our new recruit, who turned up some while later that academic year (1968/9), was a keyboards player called Andy Thorburn. Just how he was introduced to the band I’m not sure but our reputation was such by this stage that he might have found us off his own bat. Something I do remember, though, is that Howard – whether or not he was responsible for unearthing Andy – expressed strong, managerial approval of him and overrode objections from those who thought that there were rather a lot of us in the band already. But since we were genuinely intrigued at the thought of broadening our sound, these objections were only half-hearted.

As far as our style in music was concerned, the presence of Tad & Neil in the band provoked a gradual move towards original material. This process accelerated once we’d expanded from a six- into a seven-piece outfit. Our new recruit, who turned up some while later that academic year (1968/9), was a keyboards player called Andy Thorburn. Just how he was introduced to the band I’m not sure but our reputation was such by this stage that he might have found us off his own bat. Something I do remember, though, is that Howard – whether or not he was responsible for unearthing Andy – expressed strong, managerial approval of him and overrode objections from those who thought that there were rather a lot of us in the band already. But since we were genuinely intrigued at the thought of broadening our sound, these objections were only half-hearted.

Like Tad, Andy had recently arrived at Lancaster University from the States. He was, however, actually English, having lived in America for only a couple of years or so after his parents had moved out there. But this was quite long enough for him to qualify for doing his bit for Uncle Sam in the armed forces and so his parents had hastily bundled him back home as a precaution.

This technically made him a draft dodger like Tad (well, a trainee one, at any event) and enhanced the band’s prestige yet further.

The other exotic thing about Andy was that he was the owner of a rather smart sports car, a white Daimler Dart. We would gather round it admiringly – but that’s mostly all we got to do since it spent most of its time off the road, awaiting repairs that always seemed to be just beyond Andy’s financial means. It joined an ever-expanding scrapyard of other cars encircling the repair garage on the university campus at Bailrigg, all of them owned by similarly impecunious students.

As its registration number sported the letters OAT, Howard decided that Andy should be dubbed Oat Willie in honour of a character out of the underground comic book Wonder Wart Hog (a creation of the great Gilbert Shelton). But since Howard and I seemed to be the only two people who were sufficiently enthused by the adventures of The Hog of Steel to use them as a reference point, the nickname didn’t stick – no doubt to Andy’s great relief.

The main problem with Andy was his instrument – or rather lack of one. Few of the venues where we played had a functioning piano and, even if they did, satisfactory amplification was achieved only with difficulty, if at all, and so his appearances with the band sometimes had to be curtailed. However, the late 1960s represented the dying moments of the grand tradition of the faithful pub joanna and The Nag’s Head where we had our weekly residency was nothing if not traditional. There the pub’s battered old upright sat in the function room, neglected and rather in the way, save for its ability to provide useful surfaces on which to park equipment and beer glasses.

Andy gingerly tried it out and found that, whilst not exactly up to concert hall standards and prone to sending up clouds of dust, it wasn’t quite as hideously out of tune as it might have been. But he was puzzled by the fact that it seemed to lack volume, some keys in particular producing dull thuds instead of recognisable notes.

The other exotic thing about Andy was that he was the owner of a rather smart sports car, a white Daimler Dart. We would gather round it admiringly – but that’s mostly all we got to do since it spent most of its time off the road, awaiting repairs that always seemed to be just beyond Andy’s financial means. It joined an ever-expanding scrapyard of other cars encircling the repair garage on the university campus at Bailrigg, all of them owned by similarly impecunious students.

As its registration number sported the letters OAT, Howard decided that Andy should be dubbed Oat Willie in honour of a character out of the underground comic book Wonder Wart Hog (a creation of the great Gilbert Shelton). But since Howard and I seemed to be the only two people who were sufficiently enthused by the adventures of The Hog of Steel to use them as a reference point, the nickname didn’t stick – no doubt to Andy’s great relief.

The main problem with Andy was his instrument – or rather lack of one. Few of the venues where we played had a functioning piano and, even if they did, satisfactory amplification was achieved only with difficulty, if at all, and so his appearances with the band sometimes had to be curtailed. However, the late 1960s represented the dying moments of the grand tradition of the faithful pub joanna and The Nag’s Head where we had our weekly residency was nothing if not traditional. There the pub’s battered old upright sat in the function room, neglected and rather in the way, save for its ability to provide useful surfaces on which to park equipment and beer glasses.

Andy gingerly tried it out and found that, whilst not exactly up to concert hall standards and prone to sending up clouds of dust, it wasn’t quite as hideously out of tune as it might have been. But he was puzzled by the fact that it seemed to lack volume, some keys in particular producing dull thuds instead of recognisable notes.

He tried taking the lid off the top and then the panel above the keyboard but, apart from increasing the volume of dust, this action failed to increase the instrument’s carrying power significantly. Finally, he levered off the panel under the keyboard and was rewarded with an avalanche of ash, dog-ends, spent matches and empty fag packets which lay ankle deep on the ground as we coughed and spluttered through the sudden haze that had enveloped the room. It appeared that generations of drinkers had used the piano as a handy and seemingly bottomless ashtray – a bit of a comedown from its glory days of accompanying communal sing-songs, but performing a valuable function nonetheless. Andy now declared himself satisfied, although our long-suffering landlord gave vent to freely expressed emotions when he saw the mess on the floor.

We thought we’d get hold of an electric keyboard for pianoless gigs, but these were in their infancy in those days and even though Jeff kept on producing models on appro from the Morecambe music shop, the sound of them caused the other band members to utter unfeeling hoots of derision and make unkind references to Sparky’s Magic Piano. What Andy could really have done with was the sort of thing that Ray Charles played on “What’d I Say” (a Wurlitzer, I believe), but such instruments seemed to be rather thin on the ground in North Lancashire at that time. Eventually, however, Our Man in Morecambe – Geoff Normington by name – came up with something that passed muster and the latest recruit in our swelling ranks achieved a more secure place in the band.

The instrument in question was manufactured by Sydney S. Bird & Sons of Poole in Dorset, a company noted for both its sewing machines and its TV tuners but which had recently ventured into new territory. The Bird Electronic Organ may have sounded better than the products of some of its competitors, but it had its own built-in disadvantages, chief among them being a temperamental reaction to being moved – something of a handicap for a travelling band. It didn’t matter how gingerly you handled the damn thing, it would inevitably slide out of pitch at every gig and everyone had to retune their instruments to try to keep up with its latest vagaries. This gave Jay particular problems, of course, since a saxophone’s ability to be retuned is limited to how far you can adjust the mouthpiece and Jay was occasionally obliged to shave bits off the reed with a razor blade to give himself a little more scope.

We thought we’d get hold of an electric keyboard for pianoless gigs, but these were in their infancy in those days and even though Jeff kept on producing models on appro from the Morecambe music shop, the sound of them caused the other band members to utter unfeeling hoots of derision and make unkind references to Sparky’s Magic Piano. What Andy could really have done with was the sort of thing that Ray Charles played on “What’d I Say” (a Wurlitzer, I believe), but such instruments seemed to be rather thin on the ground in North Lancashire at that time. Eventually, however, Our Man in Morecambe – Geoff Normington by name – came up with something that passed muster and the latest recruit in our swelling ranks achieved a more secure place in the band.

The instrument in question was manufactured by Sydney S. Bird & Sons of Poole in Dorset, a company noted for both its sewing machines and its TV tuners but which had recently ventured into new territory. The Bird Electronic Organ may have sounded better than the products of some of its competitors, but it had its own built-in disadvantages, chief among them being a temperamental reaction to being moved – something of a handicap for a travelling band. It didn’t matter how gingerly you handled the damn thing, it would inevitably slide out of pitch at every gig and everyone had to retune their instruments to try to keep up with its latest vagaries. This gave Jay particular problems, of course, since a saxophone’s ability to be retuned is limited to how far you can adjust the mouthpiece and Jay was occasionally obliged to shave bits off the reed with a razor blade to give himself a little more scope.

The limitations of his instrument apart, there was no doubt at all about Andy’s own musical accomplishments. He was classically trained but was also very au fait with the latest developments on the American rock scene and his expertise and wide musical frame of reference made a valuable contribution to the group, especially when it came to the original numbers which, as I’ve said, were beginning to feature more and more in our repertoire. Andy & Neil were the ones who were mainly responsible for composition, whilst Tad showed a literary bent he normally liked to keep quiet about by penning suitable lyrics.

I’m afraid that I was the one who tried to resist this tendency at first as my idea had always been that our group should be a serious blues band whose music the ghost of Charley Patton might have approved of but I was gradually worn down by the enthusiasm of the others. In the end, a compromise was thrashed out whereby I was allowed to unearth authentic blues numbers to add to our repertoire provided they could be arranged to suit our developing style and, with the example before me of Taj Mahal (a musician everyone without exception admired), I readily agreed. I even managed to come up with an arrangement of such an antiquated number as Sleepy John Estes’ “Vernita Blues” that was deemed acceptable.

In turn, I did my best to grapple with the more rock-orientated style we were moving towards, which turned out to be easier than I thought it would be. Neil’s great musical hero, for instance, was by now Jerry Garcia, guitarist with the Grateful Dead. I struggled at first to adjust to such a style until Howard dug up a copy of their debut LP which proved them to have been a fairly straight-ahead blues band in their early days, a fact which helped me get my head around their current style. Funnily enough, when I finally got to see The Grateful Dead perform live (at their debut British appearance at the Hollywood Festival near Keele in 1970), much of their act was on the funky side, with even the occasional Otis Redding number surfacing from time to time.

But let me return to the point that I made at the beginning of this chapter, namely the speed of change that was characteristic of musicians and other artists at this time.

I’m afraid that I was the one who tried to resist this tendency at first as my idea had always been that our group should be a serious blues band whose music the ghost of Charley Patton might have approved of but I was gradually worn down by the enthusiasm of the others. In the end, a compromise was thrashed out whereby I was allowed to unearth authentic blues numbers to add to our repertoire provided they could be arranged to suit our developing style and, with the example before me of Taj Mahal (a musician everyone without exception admired), I readily agreed. I even managed to come up with an arrangement of such an antiquated number as Sleepy John Estes’ “Vernita Blues” that was deemed acceptable.

In turn, I did my best to grapple with the more rock-orientated style we were moving towards, which turned out to be easier than I thought it would be. Neil’s great musical hero, for instance, was by now Jerry Garcia, guitarist with the Grateful Dead. I struggled at first to adjust to such a style until Howard dug up a copy of their debut LP which proved them to have been a fairly straight-ahead blues band in their early days, a fact which helped me get my head around their current style. Funnily enough, when I finally got to see The Grateful Dead perform live (at their debut British appearance at the Hollywood Festival near Keele in 1970), much of their act was on the funky side, with even the occasional Otis Redding number surfacing from time to time.

But let me return to the point that I made at the beginning of this chapter, namely the speed of change that was characteristic of musicians and other artists at this time.

The changes that we’d introduced into our band’s musical approach went off so smoothly that we became almost unaware they’d taken place at all and it wasn’t until some kind of outside reference point intruded that we were reminded of how far we’d progressed in a short space of time. This was brought home to us most forcibly by a couple of gigs that took place about a year apart at the Embassy Ballroom in Windermere, the most north westerly of our bookings.

The first occasion must have been in the early summer of 1968 because it featured the original, settled lineup of the band with Howard on vocals and Dave on lead guitar. I suppose the very word “ballroom” should have given us some kind of clue as to what to expect but we’d become so used to student audiences and their low-energy ways, we never gave it a thought. Until, that is, we struck up with our opening number. Instantly, the space in front of us, which had up until now yawned emptily in a rather intimidating fashion, filled up, mostly with girls who placed their handbags at their feet and jigged about on the spot whilst the boys lurked around the fringes, prospecting the talent and nerving themselves up for an encounter, close or otherwise.

So far so good – quite charming in a quaint, old-fashioned sort of way, we thought. But then the jigging faltered, hesitated and finally stopped and the girls glared at us in a belligerent fashion.

“Can’t you play no soul music, then?” some of them demanded in a pause between numbers.

“No, we play blues – that’s why we’re called a blues band,” we replied smugly.

“Well play summat fast then and gerron wi’ it!” cried the local maidens and, taking a hasty look at them, we hurriedly complied with their demands.

We tentatively embarked on one of our more sprightly numbers, a Sonny Boy Williamson one called “Checkin’ Up on My Baby”. Success! The dancing began in earnest this time and the ballroom was soon awash with sweating, gyrating bodies. We spun the song out to about twice its normal length and were greeted to encouraging applause while the dancers got their breath back.

The first occasion must have been in the early summer of 1968 because it featured the original, settled lineup of the band with Howard on vocals and Dave on lead guitar. I suppose the very word “ballroom” should have given us some kind of clue as to what to expect but we’d become so used to student audiences and their low-energy ways, we never gave it a thought. Until, that is, we struck up with our opening number. Instantly, the space in front of us, which had up until now yawned emptily in a rather intimidating fashion, filled up, mostly with girls who placed their handbags at their feet and jigged about on the spot whilst the boys lurked around the fringes, prospecting the talent and nerving themselves up for an encounter, close or otherwise.

So far so good – quite charming in a quaint, old-fashioned sort of way, we thought. But then the jigging faltered, hesitated and finally stopped and the girls glared at us in a belligerent fashion.

“Can’t you play no soul music, then?” some of them demanded in a pause between numbers.

“No, we play blues – that’s why we’re called a blues band,” we replied smugly.

“Well play summat fast then and gerron wi’ it!” cried the local maidens and, taking a hasty look at them, we hurriedly complied with their demands.

We tentatively embarked on one of our more sprightly numbers, a Sonny Boy Williamson one called “Checkin’ Up on My Baby”. Success! The dancing began in earnest this time and the ballroom was soon awash with sweating, gyrating bodies. We spun the song out to about twice its normal length and were greeted to encouraging applause while the dancers got their breath back.

“That’s great,” one of them shouted. “Let’s have some more o’ that.” But, try as we might with the brisker side of our repertoire, only this one number seemed to be at the precise tempo the dancers required and we ended up playing the damn thing two or three times more as the night wore on. But no one seemed to mind the repetition.

Much to our astonishment, we were invited back the following summer. Memories must be short up in the Lake District, we thought. Still, a gig’s a gig – and a return one particularly encouraging – so we piled into the elderly Commer and set off north once more. By this time we were not only hairier and possessing a new singer and guitarist but we had a new name, Urbane Gorilla (of which more in due course). And our repertoire had changed a little, we guessed – but surely for the better, especially as some of our new songs might arguably hit that particular groove the local dancers craved. We waved cheerily at our old fans who were so pleased to see us, it appeared, they’d gathered round in front of the stage, some even sitting down just like students. Well, no doubt they’d leap to their feet and start dancing when we began playing. But not a bit of it. They just sat around, chatted and wandered about as the mood took them and were noticeably lukewarm in their applause. Whatever could be the matter?

All was revealed when a familiar-sounding voice piped up in between numbers: “Don’t you play no blues music, then?”

It seemed as if we weren’t the only ones whose musical tastes had moved on. Ah well, we consoled ourselves as we drove back to Lancaster, maybe they’ll all be into original, progressive rock next time. But there never was a next time, so we never got to find out.

These two Windermere gigs seemed to run in tandem with two others that were much farther flung and played to very different kinds of audiences. The rapid expansion in university building in the 1960s had produced a crop of establishments that felt as if they were part of a shared cultural phenomenon. Later christened The Plateglass Universities, they were known at the time simply as The New Universities and an annual event sprang up, called The New Universities Festival (or NUF) to celebrate this supposed shared outlook.

Much to our astonishment, we were invited back the following summer. Memories must be short up in the Lake District, we thought. Still, a gig’s a gig – and a return one particularly encouraging – so we piled into the elderly Commer and set off north once more. By this time we were not only hairier and possessing a new singer and guitarist but we had a new name, Urbane Gorilla (of which more in due course). And our repertoire had changed a little, we guessed – but surely for the better, especially as some of our new songs might arguably hit that particular groove the local dancers craved. We waved cheerily at our old fans who were so pleased to see us, it appeared, they’d gathered round in front of the stage, some even sitting down just like students. Well, no doubt they’d leap to their feet and start dancing when we began playing. But not a bit of it. They just sat around, chatted and wandered about as the mood took them and were noticeably lukewarm in their applause. Whatever could be the matter?

All was revealed when a familiar-sounding voice piped up in between numbers: “Don’t you play no blues music, then?”

It seemed as if we weren’t the only ones whose musical tastes had moved on. Ah well, we consoled ourselves as we drove back to Lancaster, maybe they’ll all be into original, progressive rock next time. But there never was a next time, so we never got to find out.

These two Windermere gigs seemed to run in tandem with two others that were much farther flung and played to very different kinds of audiences. The rapid expansion in university building in the 1960s had produced a crop of establishments that felt as if they were part of a shared cultural phenomenon. Later christened The Plateglass Universities, they were known at the time simply as The New Universities and an annual event sprang up, called The New Universities Festival (or NUF) to celebrate this supposed shared outlook.

We thought at first that it was only theatre groups and declaimers of poetry who attended these bashes but then we discovered rather late in the day that music groups were welcome as well and we just managed to squeeze into the lineup for the 1968 festival, which was held in Bradford. This was our farthest venture from home at the time but we broke the journey in Harrogate where we visited my parents. I was a little wary of unleashing the band on The Aged Ps but they behaved with startling self-restraint (the band members, that is), even if Jeff thought that, when my mother dumped down a turkey dish piled high with bacon, it was all for him. Embarrassment and disappointment were writ equally large on his face when he discovered the awful truth. I later found him and my father in animated conversation in the front room. It turned out that they knew people in common, including someone at Lancaster Town Hall who’d been there since my father’s time working at the local auction mart in the 1930s and of whom they took a similarly dim view.

The big lure of the Bradford NUF was the opening dance on the Friday night, because Fleetwood Mac had been booked as top of the bill. Disappointingly, however, the group cried off at the last minute (an American tour or some other piffling reason). The committee had managed to book The Savoy Brown Blues Band at short notice as a substitute but it wasn’t the same somehow. Little did I guess that, over 35 years later, I’d be gigging regularly with their pianist, Bob Hall.

The real attraction on the bill, as it turned out, was an appearance by Reparata & The Delrons, an American vocal trio touring on the back of their recent British Top 20 hit, “Captain of Your Ship”. They’d followed us across from Lancashire, in a sense, as they’d played in Morecambe earlier in the evening and the length of the Bradford dance just about gave them time to fit in both gigs, though it was a close run thing. With their shimmering, figure-hugging, silver lamé dresses, they made a deep impression on the chaps in the band and we indulged in pleasant fantasies about their singing back-up vocals for us – and even more pleasant fantasies about… But let’s not go down that particular route.

As to our own gig that weekend, that was a pretty chaotic affair. The only event we could be shoehorned into at such short notice was a poorly organised, ad hoc affair on the Saturday afternoon, which was attended, despite the relative earliness of the hour, by a cheerfully drunken audience with a low attention span.

The big lure of the Bradford NUF was the opening dance on the Friday night, because Fleetwood Mac had been booked as top of the bill. Disappointingly, however, the group cried off at the last minute (an American tour or some other piffling reason). The committee had managed to book The Savoy Brown Blues Band at short notice as a substitute but it wasn’t the same somehow. Little did I guess that, over 35 years later, I’d be gigging regularly with their pianist, Bob Hall.

The real attraction on the bill, as it turned out, was an appearance by Reparata & The Delrons, an American vocal trio touring on the back of their recent British Top 20 hit, “Captain of Your Ship”. They’d followed us across from Lancashire, in a sense, as they’d played in Morecambe earlier in the evening and the length of the Bradford dance just about gave them time to fit in both gigs, though it was a close run thing. With their shimmering, figure-hugging, silver lamé dresses, they made a deep impression on the chaps in the band and we indulged in pleasant fantasies about their singing back-up vocals for us – and even more pleasant fantasies about… But let’s not go down that particular route.

As to our own gig that weekend, that was a pretty chaotic affair. The only event we could be shoehorned into at such short notice was a poorly organised, ad hoc affair on the Saturday afternoon, which was attended, despite the relative earliness of the hour, by a cheerfully drunken audience with a low attention span.

Also, there was no time for a sound check and no clear indication from anybody about when we were supposed to start or finish. Still, we struggled through it somehow. I remember being persuaded to do a solo number at one point, which I hated. Howard told me afterwards it had been well received. “How could you tell?” I moaned. “I couldn’t hear a bloody thing. ”

Following that uncomfortable performance, I drowned my sorrows in the still-open bar, with the result that the rest of the festival seemed to pass in something of a blur. I remember some of the others disappearing off into the town for a while and coming back with tales of having discovered a coffee bar pickled in time with frothy coffee served in pyrex cups and saucers and the likes of Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent & Little Richard on the jukebox. Those of us denied this cultural highspot demanded to sample the time capsule for ourselves but, unnervingly, it couldn’t be rediscovered.

Another setback was the sudden closing of the university union bar at what seemed a ridiculously early hour. This was done ahead of schedule and without any warning, a plastic grille being lowered over the serving area but with the lights left on. This gave you a tempting view of serried ranks of bottles that were nonetheless just out of reach, like the mirage of a cool oasis that supposedly appears to a traveller in the desert driven mad by thirst. It was too much for most of our company, who went off into town to try to find a pub.

Unfortunately, it was by now after the official closing time (10.30pm in those unenlightened times), but someone had the brainwave of seeing if a drink could be had at one of the Indian restaurants that Bradford was already famous for. Eventually, one was located that agreed to serve drinks provided a meal was ordered and so everyone tucked in gratefully. After a while, though, it was observed that Jeff had become unusually quiet and, glancing up, the others discovered the most extraordinary sight. Overcome by the rigours of the day, he’d fallen asleep – face forward into his plate of curry. Roused eventually by the cries of his fellow diners, he slowly raised his face to reveal the prototype of the tandoori tan – except that the likes of Donatella Versace, who later followed Jeff’s groundbreaking fashion statement, decided to forgo the decoration of rice grains found on the original model.

Following that uncomfortable performance, I drowned my sorrows in the still-open bar, with the result that the rest of the festival seemed to pass in something of a blur. I remember some of the others disappearing off into the town for a while and coming back with tales of having discovered a coffee bar pickled in time with frothy coffee served in pyrex cups and saucers and the likes of Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent & Little Richard on the jukebox. Those of us denied this cultural highspot demanded to sample the time capsule for ourselves but, unnervingly, it couldn’t be rediscovered.

Another setback was the sudden closing of the university union bar at what seemed a ridiculously early hour. This was done ahead of schedule and without any warning, a plastic grille being lowered over the serving area but with the lights left on. This gave you a tempting view of serried ranks of bottles that were nonetheless just out of reach, like the mirage of a cool oasis that supposedly appears to a traveller in the desert driven mad by thirst. It was too much for most of our company, who went off into town to try to find a pub.

Unfortunately, it was by now after the official closing time (10.30pm in those unenlightened times), but someone had the brainwave of seeing if a drink could be had at one of the Indian restaurants that Bradford was already famous for. Eventually, one was located that agreed to serve drinks provided a meal was ordered and so everyone tucked in gratefully. After a while, though, it was observed that Jeff had become unusually quiet and, glancing up, the others discovered the most extraordinary sight. Overcome by the rigours of the day, he’d fallen asleep – face forward into his plate of curry. Roused eventually by the cries of his fellow diners, he slowly raised his face to reveal the prototype of the tandoori tan – except that the likes of Donatella Versace, who later followed Jeff’s groundbreaking fashion statement, decided to forgo the decoration of rice grains found on the original model.

Meanwhile, back at the university, things were getting increasingly blurry for me, even without one last infusion of alcohol. I remember getting very confused over the paternoster lifts in the residential block and then settling down for an all-night film show in a lecture theatre in the company of Howard and Jay. Dog-tired by this stage, I drifted in and out of consciousness, catching odd fragments of “The African Queen”, “633 Squadron” and “Topkapi”, all of which merged disconcertingly into one surreal whole. The show was scheduled to finish at 6.30 am, leaving a nasty half hour gap before breakfast was served. We were all awake and shivering in the early morning chill by this stage. How on earth would we fill in that yawning chasm before we could shovel some hot food down our throats? But the projectionist had a trick up his sleeve. The lights suddenly dimmed again and a Tom & Jerry cartoon was shown. And then another. And another. Weakened by lack of sleep, hangovers, hunger, cold and sensory overload, we all grew hysterical and begged for mercy. Some members of the audience with lower sanity thresholds had to be carted off to recover quietly in odd corners. All in all, not much of a gig but certainly a memorable weekend.

The following year’s NUF, held at the University of Kent, was something of a contrast. Instead of being based in the centre of a Northern industrial city it was on a purpose-built rural campus perched on a hillside – like Bailrigg, Lancaster University’s campus, only grander and posher and reeking of wealth and privilege and with the ancient town of Canterbury spread out picturesquely on the plain beneath.

No doubt this was of little interest to those falling out of the trusty old Commer after its epic journey down from Lancaster. I wouldn’t know: I was one of the ones who’d perhaps wisely elected to take advantage of a coach laid on for participating students. Unlike the Bradford bash, there was quite a Lancastrian contingent at Kent, including the cast of that year’s popular rag revue and other delights. But the first thing we noticed on the Friday night as we all gathered together was that, notwithstanding our affluent surroundings, the budget seemed to be decidedly slimmer than the previous year’s.

There was no pretence at booking topflight acts for the opening dance, for instance. The main turns, as I recall, were Steamhammer and Jellybread – both pretty good bands and with debut albums already under their belts, but not exactly in the world-dominating league.

The following year’s NUF, held at the University of Kent, was something of a contrast. Instead of being based in the centre of a Northern industrial city it was on a purpose-built rural campus perched on a hillside – like Bailrigg, Lancaster University’s campus, only grander and posher and reeking of wealth and privilege and with the ancient town of Canterbury spread out picturesquely on the plain beneath.

No doubt this was of little interest to those falling out of the trusty old Commer after its epic journey down from Lancaster. I wouldn’t know: I was one of the ones who’d perhaps wisely elected to take advantage of a coach laid on for participating students. Unlike the Bradford bash, there was quite a Lancastrian contingent at Kent, including the cast of that year’s popular rag revue and other delights. But the first thing we noticed on the Friday night as we all gathered together was that, notwithstanding our affluent surroundings, the budget seemed to be decidedly slimmer than the previous year’s.

There was no pretence at booking topflight acts for the opening dance, for instance. The main turns, as I recall, were Steamhammer and Jellybread – both pretty good bands and with debut albums already under their belts, but not exactly in the world-dominating league.

We decided we could have held our own in such company, had the opportunity arisen, but we were soon to learn that spontaneity wasn’t a commodity that was much approved of at Kent, which resembled nothing so much as a finishing school for the more conventional sons and daughters of the comfortably-heeled denizens of the Home Counties stockbroker belt.

Before we found out about that, though, we were introduced to the Spartan nature of the accommodation. Those of us used to the rigours of the public school system thought nothing of roughing it for a night or two – all jolly stuff, like a weekend scout or cadet camp. But those from a grammar school or secondary modern background looked rather askance at what was laid out for us. In what seemed usually to be used as a seminar room – going by the amount of tables and chairs stacked around the walls – camp beds had been laid out in serried ranks. There was also strict segregation between the sexes, something we weren’t used to in Lancaster’s more liberal climate. Not that it mattered for most of us that particular weekend but Celia had, of course, come down with Jeff and the thought of being separated was intolerable for the lovebirds. So Jeff, ever the handyman, constructed a sort of den made of upended chairs and tables to create a little privacy.

Come the dawn (well, some considerable time afterwards, actually) we sought out what entertainment might be laid on. Not finding anything very much, the old Mickey Rooney spirit reasserted itself and we decided to provide our own. We found a rather pleasant spot out of doors next to some attractive shrubbery with a small pond in the background and, after Jeff and Roy had discovered a handily adjacent power point, decided to treat our fellow festival-goers to a little al fresco free music. But no sooner had we struck up and attracted the beginnings of a promising crowd than the ever-present student apparatchiks responsible for the smooth running of the festival came rushing towards us, waving their arms. No, no, they cried, we mustn’t play here. It wasn’t scheduled. Horrors! These awful hairy creatures from the North were about to engage in spontaneity. Out of the question.

We’d just embarked upon a spirited debate on the pros and cons of being uptight arseholes when our metaphysical discussion was interrupted by another student wearing a more important-looking badge than her colleagues. On no account must we play another note, she declared firmly, because Arnold

Before we found out about that, though, we were introduced to the Spartan nature of the accommodation. Those of us used to the rigours of the public school system thought nothing of roughing it for a night or two – all jolly stuff, like a weekend scout or cadet camp. But those from a grammar school or secondary modern background looked rather askance at what was laid out for us. In what seemed usually to be used as a seminar room – going by the amount of tables and chairs stacked around the walls – camp beds had been laid out in serried ranks. There was also strict segregation between the sexes, something we weren’t used to in Lancaster’s more liberal climate. Not that it mattered for most of us that particular weekend but Celia had, of course, come down with Jeff and the thought of being separated was intolerable for the lovebirds. So Jeff, ever the handyman, constructed a sort of den made of upended chairs and tables to create a little privacy.

Come the dawn (well, some considerable time afterwards, actually) we sought out what entertainment might be laid on. Not finding anything very much, the old Mickey Rooney spirit reasserted itself and we decided to provide our own. We found a rather pleasant spot out of doors next to some attractive shrubbery with a small pond in the background and, after Jeff and Roy had discovered a handily adjacent power point, decided to treat our fellow festival-goers to a little al fresco free music. But no sooner had we struck up and attracted the beginnings of a promising crowd than the ever-present student apparatchiks responsible for the smooth running of the festival came rushing towards us, waving their arms. No, no, they cried, we mustn’t play here. It wasn’t scheduled. Horrors! These awful hairy creatures from the North were about to engage in spontaneity. Out of the question.

We’d just embarked upon a spirited debate on the pros and cons of being uptight arseholes when our metaphysical discussion was interrupted by another student wearing a more important-looking badge than her colleagues. On no account must we play another note, she declared firmly, because Arnold

Wesker was addressing a meeting in a nearby building and couldn’t hear himself talk.

“Well, tell him to speak up!” we retorted callously, but our witticisms fell upon stony ground and we were obliged to unplug, lest our leads be confiscated by the Public Nuisance Police.

.jpg) After they realised we were going to comply with their wishes and not beat them up after all, despite some muttered threats from Terry (drummers! I don’t know!), the apparatchiks became more conciliatory and promised we would get extra publicity for our scheduled gig later that afternoon in return for being good.

After they realised we were going to comply with their wishes and not beat them up after all, despite some muttered threats from Terry (drummers! I don’t know!), the apparatchiks became more conciliatory and promised we would get extra publicity for our scheduled gig later that afternoon in return for being good.

This was another al fresco affair, as it turned out, but this time with a rudimentary stage provided in front of what was probably the most unattractive building on the entire campus. But, never mind, the thought police were as good as their word and quite a fair crowd had already gathered as we tooled up, ready for action. Unlike the equivalent event at the previous year’s festival, the organisation went smoothly, the audience was both sober and attentive and the whole thing was declared a success. A couple of members of Jellybread, who’d made our acquaintance the night before, even showed up and jammed with us on a few numbers. One of them was a tall, skinny guy with long, sticky-out hair who sang and played the harmonica, I seem to recall, but I wasn’t sure which one he was.

“Well, tell him to speak up!” we retorted callously, but our witticisms fell upon stony ground and we were obliged to unplug, lest our leads be confiscated by the Public Nuisance Police.

.jpg) After they realised we were going to comply with their wishes and not beat them up after all, despite some muttered threats from Terry (drummers! I don’t know!), the apparatchiks became more conciliatory and promised we would get extra publicity for our scheduled gig later that afternoon in return for being good.

After they realised we were going to comply with their wishes and not beat them up after all, despite some muttered threats from Terry (drummers! I don’t know!), the apparatchiks became more conciliatory and promised we would get extra publicity for our scheduled gig later that afternoon in return for being good.

This was another al fresco affair, as it turned out, but this time with a rudimentary stage provided in front of what was probably the most unattractive building on the entire campus. But, never mind, the thought police were as good as their word and quite a fair crowd had already gathered as we tooled up, ready for action. Unlike the equivalent event at the previous year’s festival, the organisation went smoothly, the audience was both sober and attentive and the whole thing was declared a success. A couple of members of Jellybread, who’d made our acquaintance the night before, even showed up and jammed with us on a few numbers. One of them was a tall, skinny guy with long, sticky-out hair who sang and played the harmonica, I seem to recall, but I wasn’t sure which one he was.

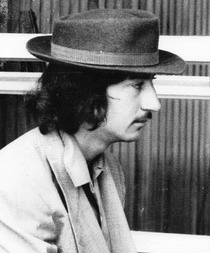

.jpg) You can see from the accompanying photographs (rare colour shots of the band in action!) that it was a very seemly sort of affair, especially compared to some of our more riotous gigs. Some new equipment had clearly put in an appearance by this stage – though how I was later to regret disposing of those wonderful old Vox AC 30s. We were at this point using stuff made by Impact, a rather short-lived company based in London. Not that we objected too much since we hadn’t paid for it. Howard had managed to persuade the student financial committee that it was absolutely essential that our aging speakers and amps be upgraded and they’d obligingly coughed up the necessary funding. Unfortunately, some keen and public-spirited recent appointee to the committee then spoiled it all by declaring that the new equipment should be available to all and not be for the exclusive use of one set of students. In vain did Howard attempt to browbeat this Goody Two-Shoes, who retaliated by simply announcing to the student body at large that there was sound equipment available for whoever chose to make use of it.

You can see from the accompanying photographs (rare colour shots of the band in action!) that it was a very seemly sort of affair, especially compared to some of our more riotous gigs. Some new equipment had clearly put in an appearance by this stage – though how I was later to regret disposing of those wonderful old Vox AC 30s. We were at this point using stuff made by Impact, a rather short-lived company based in London. Not that we objected too much since we hadn’t paid for it. Howard had managed to persuade the student financial committee that it was absolutely essential that our aging speakers and amps be upgraded and they’d obligingly coughed up the necessary funding. Unfortunately, some keen and public-spirited recent appointee to the committee then spoiled it all by declaring that the new equipment should be available to all and not be for the exclusive use of one set of students. In vain did Howard attempt to browbeat this Goody Two-Shoes, who retaliated by simply announcing to the student body at large that there was sound equipment available for whoever chose to make use of it.

We were forced to beat a hasty path back to Mr. Normington’s emporium and invest heavily in some terrifyingly powerful Marshall 100 watt amps and the like. This meant that the prospect of earning serious money out of our musical activities was suddenly snatched away from us because of the necessity of paying off the hire purchase on our new investment. This turn of events caused the impecunious Tad particular grief, so some small dispensation was arranged in his favour lest he should starve and therefore find it difficult to sing.

Meanwhile, the end of our University of Kent gig – agreeable though it had turned out to be – signalled the imminent end of our trip down to the Deep South. There wasn’t a great deal left for us to do afterwards in any case so, since there was such a long way to travel home (and Roy had begun complaining about the unhappy lot of a roadie), the van contingent was obliged to leave a little on the early side.

Those who remained took in the final Sunday afternoon concert, which, yet again, was held outside. Were they all fresh air fiends at Kent? Did they lack suitable venues? Did they not like the thought of so many sweaty, alien bodies befouling their hallowed cloisters? We couldn’t say. The concert in question was billed as a folk music event although it was as eclectic as most events were at that time. The bill consisted of the one-man blues band Duster Bennett, the madcap musical anarchist Ron Geesin, whose contempt for the ever-present jobsworths won him much approval (“Dinnae touch the microphones!” he intoned solemnly, before belabouring one with a drumstick); also Bridget St. John (a recent discovery of John Peel) and, top of the bill, Ralph McTell, who’d just had his third album released and who at this point was crossing over from being essentially a blues and ragtime guitarist into becoming a singer-songwriter.

Those who remained took in the final Sunday afternoon concert, which, yet again, was held outside. Were they all fresh air fiends at Kent? Did they lack suitable venues? Did they not like the thought of so many sweaty, alien bodies befouling their hallowed cloisters? We couldn’t say. The concert in question was billed as a folk music event although it was as eclectic as most events were at that time. The bill consisted of the one-man blues band Duster Bennett, the madcap musical anarchist Ron Geesin, whose contempt for the ever-present jobsworths won him much approval (“Dinnae touch the microphones!” he intoned solemnly, before belabouring one with a drumstick); also Bridget St. John (a recent discovery of John Peel) and, top of the bill, Ralph McTell, who’d just had his third album released and who at this point was crossing over from being essentially a blues and ragtime guitarist into becoming a singer-songwriter.

After the concert was over and while we were waiting for the coach to arrive to take us back North, I met up with a fellow student and folk-blues guitarist from a Scottish university. We swapped ideas, with him revealing some of the secrets of Robert Johnson’s guitar playing and me showing him some of the Blind Boy Fuller licks Ralph McTell had been using in his concert. We also exchanged addresses but, of course, I’ve long since lost his and can’t even remember what he was called. That combination of being generous over sharing knowledge but spendthrift of opportunities seems to me to be very typical of those days.

Those who remained took in the final Sunday afternoon concert, which, yet again, was held outside. Were they all fresh air fiends at Kent? Did they lack suitable venues? Did they not like the thought of so many sweaty, alien bodies befouling their hallowed cloisters? We couldn’t say. The concert in question was billed as a folk music event although it was as eclectic as most events were at that time. The bill consisted of the one-man blues band Duster Bennett, the madcap musical anarchist Ron Geesin, whose contempt for the ever-present jobsworths won him much approval (“Dinnae touch the microphones!” he intoned solemnly, before belabouring one with a drumstick); also Bridget St. John (a recent discovery of John Peel) and, top of the bill, Ralph McTell, who’d just had his third album released and who at this point was crossing over from being essentially a blues and ragtime guitarist into becoming a singer-songwriter.

Those who remained took in the final Sunday afternoon concert, which, yet again, was held outside. Were they all fresh air fiends at Kent? Did they lack suitable venues? Did they not like the thought of so many sweaty, alien bodies befouling their hallowed cloisters? We couldn’t say. The concert in question was billed as a folk music event although it was as eclectic as most events were at that time. The bill consisted of the one-man blues band Duster Bennett, the madcap musical anarchist Ron Geesin, whose contempt for the ever-present jobsworths won him much approval (“Dinnae touch the microphones!” he intoned solemnly, before belabouring one with a drumstick); also Bridget St. John (a recent discovery of John Peel) and, top of the bill, Ralph McTell, who’d just had his third album released and who at this point was crossing over from being essentially a blues and ragtime guitarist into becoming a singer-songwriter.

After the concert was over and while we were waiting for the coach to arrive to take us back North, I met up with a fellow student and folk-blues guitarist from a Scottish university. We swapped ideas, with him revealing some of the secrets of Robert Johnson’s guitar playing and me showing him some of the Blind Boy Fuller licks Ralph McTell had been using in his concert. We also exchanged addresses but, of course, I’ve long since lost his and can’t even remember what he was called. That combination of being generous over sharing knowledge but spendthrift of opportunities seems to me to be very typical of those days.

( ... to be continued ... )